Renovations offer the opportunity to move with the times and install home automation. But is it really that simple? What technical challenges will homeowners face? And where are the limits of what's possible? Christian Ziegler from Hettlingen took the plunge into the future and automated his 30-year-old detached house.

Hettlingen is a tranquil village just outside Winterthur. The Ziegler family lives and works here in a quiet residential area of single-family homes. Both Christian and Manuela Ziegler are trained electricians; together they run All-Com AG. The company is based in the family home and specializes in building automation. Christian Ziegler recalls: "When I started my own business, I was practically burned at the stake. 'Smart homes? Nobody needs that!' was a common refrain. But I had the feeling that home automation was normal. It wasn't some kind of devil's work." His intuition proved correct for the 49-year-old father of two daughters: For 16 years, the company has been successfully operating in this field. "We primarily automate new buildings, as that's pretty much standard practice these days," says Christian Ziegler. The situation is somewhat different with existing buildings. "Automation is rarely considered for renovations and refurbishments." He can only speculate as to why: "Many property owners don't seem to realize that this is feasible."

Not difficult, but time-consuming

The Ziegler family, who bought their own house about six years ago, have proven the opposite, automating just about everything over the past two and a half years: room temperature control, blinds, multimedia systems, appliances like the electric lawnmower that autonomously mows the lawn in front of the patio, and the lighting. It wasn't difficult to implement, just time-consuming. Christian Ziegler explains: "We only had floor plans available, meaning plans with marked sockets, switches, and junction boxes, but no wiring diagrams. So, in every room, we first had to unscrew the existing appliances to figure out what we needed. Then we ordered the materials and installed them. Because of the children, we couldn't leave the electrical wiring exposed. So, we did everything twice: first, we unscrewed everything and saw what was needed, then screwed it back together, ordered the parts, unscrewed it again, installed everything, and finally programmed it."

Networked thanks to KNX

The Zieglers opted for KNX – a portmanteau of Konnex – and the associated ETS automation software for their home automation. This bus system separates device control and power supply into two networks: the AC power grid and the DC control network, also known as the fieldbus or bus line. All devices to be controlled are connected via this bus and exchange data. The function of each bus device is determined by specific programming. Actuators, or drive units that convert an electrical signal into mechanical movements, are installed between the devices and the mains voltage. These actuators are also connected to the KNX bus and receive their data in the form of telegrams directly from a sensor, such as a motion detector or thermostat.

500 producers, one standard

The bus system is standardized and has been on the market for 30 years. Therefore, it can be used to network all kinds of building services from various manufacturers – provided they have the corresponding certification from the KNX Association. Christian Ziegler says: "Worldwide, there are about 500 manufacturers whose devices support the KNX standard." Furthermore, it's possible to connect wired and wireless components. This is particularly advantageous when conduit is not optimally routed. This was the case, for example, with the blinds in the family's house: Although they were already electrified and could therefore be easily converted to automated control, the existing 230V conduit was inconveniently located. Decentralized wireless actuators solved this problem.

A house full of scenes

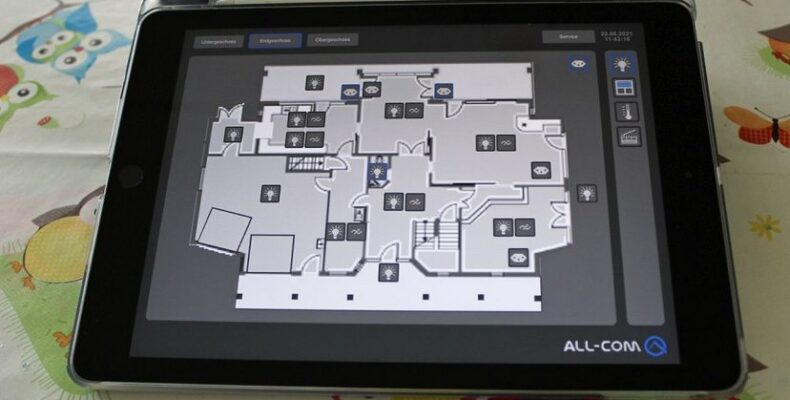

Conventional light switches are a rarity in the Ziegler family home. Most have been replaced by KNX push buttons, whose LEDs glow yellow, blue, and violet. Unlike a light switch, a push button doesn't close electrical circuits, but rather sends impulses to activate a process—or a scene, as Christian Ziegler calls it. He explains: "For us, yellow means light, blue means blinds, and violet means scenes." The electrician programmed the latter himself. "That's not really difficult either, more like a matter of diligence," he says. "If we want to define a new scene or change an existing one, we can easily do it on our laptop, tablet, or smartphone." But a one-week KNX basic course is still a worthwhile investment. "The rest is learning by doing." In the dining area, Christian Ziegler presses different scenes. The dining scene brightens the lights above the dining table, the dinner scene dims them again, and the everyday scene switches on additional lights in the kitchen. All these scenes can also be activated or deactivated via app on a smartphone or tablet. Christian Ziegler takes out his smartphone and opens the corresponding app. The menu displays the floors and individual rooms. He navigates to his daughters' playroom and taps on the playroom scene, whereupon the lights and music are switched on.

Only purple buttons now!

The next stop on the tour is the entryway, where Christian Ziegler activates the "Briefly Away" scene. "We press this button when we go shopping, for example. The lights go out, the music system is switched off, and the blinds and the camera on the patio are activated," he says. "And if we forget, we can also select the scene later on our smartphones." Within the house, this works via Wi-Fi; outside, it's done via a VPN connection to the server located in the basement. At the button next to the stairs to the upper floor, he selects "Go Up." The scene is defined so that only a few lights remain on in the kitchen, while the lights by the stairs brighten. Once upstairs in the bedroom, he presses a button on the switch above the bed. The "Good Night" scene switches off all the lights in the house and activates the Sonos speaker. Soft music begins to play. "That's our bedtime music," says the father, summing up: "That's basically how we operate." For us, practically only the purple buttons are left

There are also pitfalls

The tour demonstrates that retrofitting home automation is possible with little to no structural modifications. Christian Ziegler explains: "We didn't make any structural changes at all, just drilled a few holes here and there. I didn't pick up a sledgehammer and chisel any channels into the walls." However, he acknowledges that there are some pitfalls. "For example, if you don't know the layout of the wiring, you have to figure it out first." He adds that it also requires time and money. "The original electrical installation in our house cost around 70,000 Swiss francs when it was built in 1991. That was quite a lot even back then. Looking at the components we installed and the time we spent, I'm easily at double that amount," Christian Ziegler calculates. "In a new build," he estimates, "the additional costs for electrical installation and automation would amount to about ten percent of the total construction cost."

It's the basics that matter

There are few limitations to automation in existing buildings. Christian Ziegler says: "Of course, it's easier if the basic infrastructure is already in place. For example, electric blinds, which can be easily automated." If such infrastructure isn't present—for instance, in an apartment building from the 1970s—it becomes expensive. "You'd first have to supply the blinds with electricity, for example. In such buildings, I would recommend waiting until a complete renovation is already planned. Because then you're going to be cutting channels into the walls or lowering the ceiling anyway, and you can install the automation components at the same time."

A fun gadget

The question arises whether this not inconsiderable additional investment is worthwhile, for example, in terms of energy savings. Christian Ziegler says no. "That would require additional construction measures, such as an energy-efficient roof renovation, which we have already done." Automation alone has little impact on energy consumption. "We might save a little energy when we travel to the Engadine for a few days. Then we lower the room temperature and only raise it again when we're on our way home." But saving energy wasn't the reason the family decided to make their house smart. "I think it's simply part of modern living. Besides, our house serves as a kind of showroom for our customers." He's convinced: "You can't sell building automation at a desk. Customers have to experience it." And, of course, a smart home also brings greater living comfort. Christian Ziegler: "If one of our garage doors is open, I see a red bar on my smartphone." With a swipe, I can close the gate without having to get up. That's really convenient. Besides, it's really fun to live in an automated house. I certainly wouldn't want to be without it anymore